Angular momentum#

What you need to know

Angular momentum plays a central role in both classical and quantum mechanics. In classical mechanics, all isolated systems conserve angular momentum (as well as energy and linear momentum); this fact reduces considerably the amount of work required in calculating trajectories of planets, rotation of rigid bodies, and many more.

Similarly, in quantum mechanics, angular momentum plays a central role in understanding the structure of atoms, as well as other quantum problems that involve rotational symmetry. Like other observable quantities, angular momentum is described in QM by an operator. This is in fact a vector operator, similar to momentum operator. However, contrary to the linear momentum operator, the three components of the angular momentum operator do not commute!

In QM, there are several angular momentum operators: the total angular momentum (usually denoted by \(J\)), the orbital angular momentum (usually denoted by \(L\) ) and the intrinsic, or spin angular momentum (denoted by \(S\)). This spin has no classical analogue! Confusingly, the term “angular momentum” can refer to either the total angular momentum, or to the orbital angular momentum.

Classical angular momentum#

In classical mechanics, the angular momentum is defined as:

Here \(\vec{r}\) is the position and \(\vec{v}\) the velocity of the mass \(m\).

To evaluate the cross, we write down the Cartesian components:

The cross product is convenient to write using a determinant:

where \(\vec{i}, \vec{j}\) and \(\vec{k}\) denote unit vectors along the \(x, y\) and \(z\) axes.

The Cartesian components can be identified as:

The square of the angular momentum is given by:

Quantum angular momentum#

In quantum mechanics, the classical angular momentum is replaced by the corresponding quantum mechanical operator (see the previous ``classical - quantum’’ correspondence table). The Cartesian quantum mechanical angular momentum operators are:

In spherical coordinates, the angular momentum operators can be written in the following form (derivations are quite tedious but just math):

Note that the choice of \(z\)-axis (``quantization axis’’) here was arbitrary. Sometimes the physical system implies such axis naturally (for example, the direction of an external magnetic field). The following commutation relations can be shown to hold:

Exercise Prove that the above commutation relations hold.

Note that equations imply that it is not possible to measure any of the Cartesian angular momentum pairs simultaneously with an infinite precision (the Heisenberg uncertainty relation).

It is possible to find functions that are eigenfunctions of both \(\vec{\hat{L}}^2\) and \(\hat{L}_z\). It can be shown that for \(\vec{\hat{L}}^2\) the eigenfunctions and eigenvalues are:

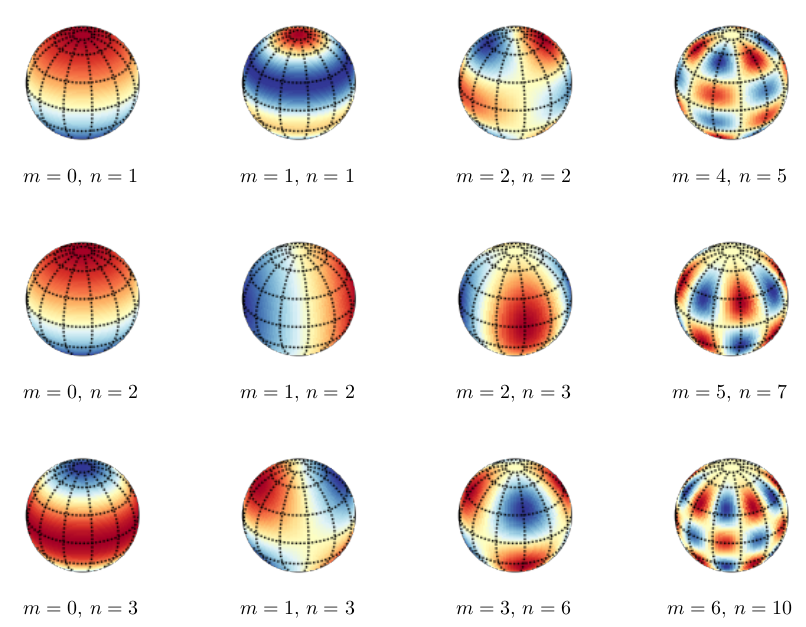

where \(l\) is the angular momentum quantum number and \(m\) is the magnetic quantum number . Note that here \(m\) has nothing to do with magnetism but the name originates from the fact that (electron or nuclear) spins follow the same laws of angular momentum. Functions \(Y_l^m\) are called spherical harmonics. Examples of spherical harmonics with various values of \(l\) and \(m\) are given below (with Condon-Shortley phase convention

Spherical harmonics#

The functions \(Y_{J,m}(\theta,\phi)\) are spherical harmonics that frequently occur in problems with spherical symmetry as the convenient basis of expansion. Spherical harmonics are important in many theoretical and practical applications, e.g., the representation of multipole electrostatic and electromagnetic fields, computation of atomic orbital electron configurations, representation of gravitational fields, MRI imaging for streamline tractography, and the magnetic fields of planetary bodies and stars.

Spherical harmonics consist of associated Legendre polynomials (\(\theta\) part) and complex exponential (\(\phi part\))

In and physical science, spherical harmonics are defined on the surface of a sphere. The spherical harmonics are a complete set of on the sphere, and thus may be used to represent functions defined on the surface of a sphere, just as circular functions (sines and cosines) are used to represent functions on a circle via Fourier series. Like the sines and cosines in the Fourier series, the spherical harmonics may be organized by (spatial) angular frequency, as seen in the rows of functions in the illustration on the right.

The following relations are useful when working with spherical harmonics:

Operating on the eigenfunctions by \(L_z\) gives the following eigenvalues for \(L_z\):

These eigenvalues are often denoted by \(L_z\) (\(= m\hbar\)). Note that specification of both \(L^2\) and \(L_z\) provides all the information we can have about the system.

Visual account of orthogonality of spherical harmonics#

Mathematically, the spherical harmonics contain alternating odd and even pairs of Legendre polynomials similar to Hermite polynomials. Visually, the spherical harmonics clearly show nodal lines with increasing quantum numbers, a pattern that we have seen on the examples of a particle in a box and harmonic oscillator. Using the symmetry argument, one can already tell that the product of any two different spherical harmonics integrated over the sphere will be zero!